The ICU is no place to get good rest, as anyone who has worked, visited or stayed in one knows.

Alarms designed to alert clinicians disrupt patient sleep, adding to their stress and disorientation. The alarms are shrill, frequent and often false.

What if an in-ear device could block a specific alarm sound – in this case, the “red” crisis alarm from patient monitors – yet not interfere with speech and normal environmental sounds?

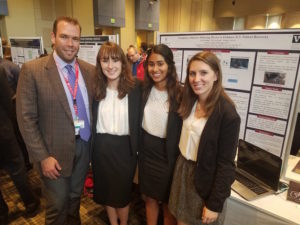

For their senior design project, three biomedical engineering majors, now Vanderbilt School of Engineering graduates, set out to prove it could be done. And they did.

Working under the direction of Joe Schlesinger, a critical care physician and assistant professor of anesthesiology at Vanderbilt University Medical Center, they used real-time audio signal processing and filters to create a workable in-ear device. Next, the team simulated an ICU environment with all its alarms and bustle and measured quantitative as well as qualitative reactions from classmates who had agreed to be test “patients.”

The results showed clinical and statistical improvement in both filtering out the alarms and improving participants’ ability to hear speech.

Schlesinger and the trio – Elizabeth Reynolds, Brittany Sweyer and Alyna Pradhan – presented their work last month at Pennsylvania State University to the largest audio conference in the world. The team’s paper, with all three students (now graduates) listed as Schlesinger’s coauthors, had been accepted as a full presentation at the 23rd International Conference on Auditory Display.

“We wanted to create a way that clinicians would still be alerted to necessary patient alarms, while providing a better environment for the patient’s healing process,” Schlesinger said. “The question became — how do we filter out the alarms from the patient experience without harming the patient’s ability to hear and comprehend speech as well as be in tune to other environmental sounds?”

Legacy project on a tight deadline

An accomplished jazz pianist, Schlesinger is involved with multiple research projects in which sound is the common thread. The 2017 design team was the third group of biomedical engineering seniors to work with him, and the next team will pick up the ICU alarm project and work on a production prototype.

The ongoing nature of the research appealed to Reynolds.

“I really liked the idea of getting to continue and refine a project that is based on a large-scale topic with far-reaching applications,” she said. “I also appreciated how the project was easily understood outside the medical field – anyone who has been in the ICU, as either a patient or a visitor, knows that medical alarms are both incessant and irritating.”

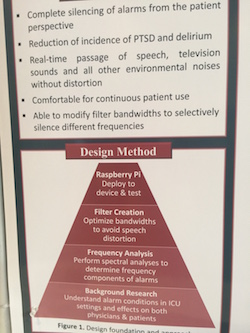

A short timeframe and long list of design requirements made the project especially challenging. Among the hurdles:

- The in-ear technology had to be comfortable for continuous wear, including while asleep.

- The device could not interfere with the patient’s ability to hear speech and other environmental sounds, such as the TV.

- The technology needed to process sounds in real-time because delays could disorient and further stress the patient.

- A detector within the device would activate it only when alarm sounds were present.

The students also had to learn a new subject quickly. As BME undergraduates, they had not encountered digital signal processing. Computer science and electrical engineering professors helped them bridge that gap.

“The most challenging part as a team was moving from the large problem that these clinical alarms presented to a concrete solution that could be achieved in a year’s time,” Sweyer said.

Collaboration across disciplines and institutions

The project also exposed the undergraduates to the increasingly collaborative nature of research, with connections to the Vanderbilt School of Medicine; the Department of Hearing & Speech Sciences; the Music, Mind and Society Program; and multiple departments within the School of Engineering.

Additionally, the students traveled with Schlesinger to meet with a collaborator at l’École de technologie supérieure (ÉTS), an engineering undergraduate and graduate institution in Montréal.

A graduate student researcher there is refining the audio filters this summer, and a new Vanderbilt BME team will take the “proof of concept” work and build on it.

The immediate goal is a comfortable, inexpensive and reusable wireless device that digitally subtracts alarm sound waves while preserving and improving speech comprehension.

Schlesinger hopes other researchers will use the work to study large ICU patient populations. A related project will investigate in-ear technology for clinicians.

On the provider side, alarm prevalence adds to stress but also desensitizes medical staff to the repetitive sound. On the patient side, constant alarms add to ICU-related delirium, PTSD and anxiety.

That the BME students achieved “clinically and statistically significant results” in such a short time and had their work accepted to the premier global auditory conference is impressive, Schlesinger said. “It far exceeded my expectations,” he said.

Take a look at Schlesinger’s research and what the BME team members had to say about the alarm project:

Media Inquiries:

Pamela Coyle, (615) 343-5495

Pam.Coyle@Vanderbilt.edu

Twitter @VUEngineering