Vanderbilt civil and environmental engineers have concluded that cities in Middle and East Tennessee with waterborne access to petroleum products were far less affected by the disruption of the Colonial Pipeline shutdown in May 2021 than other regional markets. The research was conducted as part of a case study on resilience strategies for navigable portions and associated infrastructure of the Cumberland/Tennessee river couplet system.

Janey Camp and Craig Philip, research associate professor and research professor, respectively, of civil and environmental engineering, are leading the ongoing work. Research and data analysis on fuel shortages due to the Colonial Pipeline disruption was conducted by civil engineering doctoral student Miguel Moravec. Philip is director of the Vanderbilt Center for Transportation and Operational Resiliency, and Camp is co-director.

The Colonial Pipeline is the only pipeline serving southeastern U.S. markets, providing at least 70 percent of fuel to the region. For Tennessee, reliance on Colonial is even more pronounced: 80 percent of gas in the Middle Tennessee region was supplied by Colonial in 2019. Contemporary reliance on Colonial and previous events including an explosion in 2016 and Hurricane Harvey in 2017 made studying the pipeline in the context of port resilience an obvious choice.

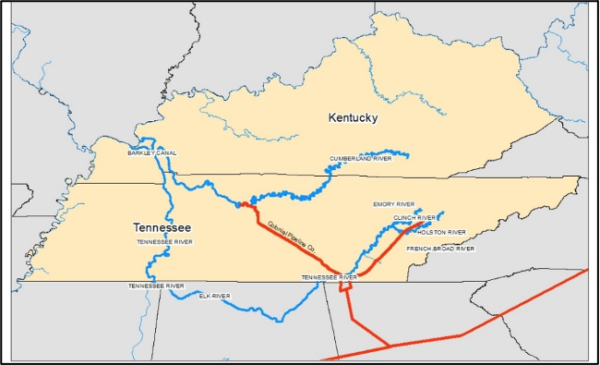

To understand the impact of fuel shortages caused by the May 7 shutdown in the region Moravec focused on six cities; Nashville, Chattanooga, Knoxville, Raleigh, Charlotte and Asheville. Cities in Tennessee each have some level of waterborne access to fuel while all three cities in North Carolina rely on fuel delivered by pipeline.

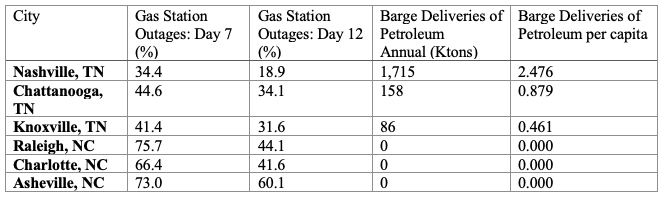

Using data provided by the US Army Corps of Engineers and Gas Buddy, a technology company providing real-time international fuel prices, Moravec found wide disparities between cities in Tennessee and North Carolina.

“Our preliminary findings suggest that there is a statistically significant relationship between a city’s annual waterborne petroleum volumes (adjusted per capita) and the proportion of gas station outages during this year’s disruption of the Colonial Pipeline, especially as the closure stretched on to its second week,” Moravec said.

Nashville, which has the largest waterborne fuel volumes per capita of the cities studied reported only 18.9 percent of stations out of fuel by the twelfth day of the disruption while Knoxville, which receives less waterborne fuel, reported a 31.6 percent outage on the same day. Cities in North Carolina with no waterborne access reported outages as high as 40 to 60 percent that same day.

“We cannot underestimate the need for multiple transport delivery options that allow essential goods and products to travel across the country,” Camp said. “This analysis demonstrates that ports, especially inland terminals, continue to be a critical factor in the nation’s supply chain. American cities and states will need to keep this in mind as they plan for long-term, resilient infrastructure investments over time.”

With a 35-year career in intermodal logistics and as a member of the Transportation Research Board’s Executive Committee and Marine Board, Craig Philip is familiar with the importance of supply chain resilience strategies. “Looking at examples of logistics resiliency or the impact of disruption events puts the need for infrastructure reinvestment into context,” said Philip. “Our goal with this work is to contribute to a national Port Resilience Guide to be published by the US Department of Homeland Security and US Army Corps of Engineers so that regions with maritime options aren’t caught flat-footed at those times when they need to be most prepared.”

In a virtual roundtable meeting with stakeholders on the project including Ben Bolton, energy programs administrator for the Tennessee Department of Environment & Conservation, and Megan Simpson, Chief, Navigation Section, Technical Support Branch of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers – Nashville Branch, everyone agreed on the importance of rapid response and clear communication as one of the critical lessons learned from the shutdown. This, according to the group, will be the single most important factor in mitigating future potential crises.

The research supporting the case study’s development is funded by the DHS Coastal Resilience Center of Excellence at UNC-Chapel Hill.