A new lung-on-a-chip system that includes immune responses that mimic what occurs in the human body may help vastly advance pre-clinical efforts to investigate treatments for severe viral infections like influenza.

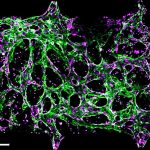

Organ-on-a-chip models—essentially microscopic versions of a lung, heart or other essential human tissues—allow researchers to investigate various aspects of promising new avenues of drug discovery long before moving into human trials.

Now, research co-directed by Krish Roy, the Bruce and Bridgitt Dean of Vanderbilt University’s School of Engineering, and Ankur Singh, director of Georgia Tech’s Center for Immunoengineering, has pioneered a way to add an immune system component to lung-on-a-chip systems. Long a missing piece of lung-on-a-chip models, adding immune responses propels what researchers working on prevention and treatment for severe viral infections can accomplish with these systems.

A new study describing the development, “An immune-competent lung-on-a-chip for modelling the human severe influenza infection response,” was published in Nature Biomedical Engineering on Sept. 23, 2025. Rachel Ringquist, Roy’s former graduate student, and now a postdoctoral fellow with Singh, led the work as part of her doctoral dissertation.

“This unique lung-on-a-chip model opens new, preclinical pathways of discovery that will allow researchers to better understand the interplay of immune responses to severe viral infections and evaluate critical antiviral treatments,” said Roy, who is also University Distinguished Professor of Biomedical Engineering and Pathology, Microbiology and Immunology at Vanderbilt University School of Medicine.

Singh, the Carl Ring Family Professor at Georgia Tech’s George W. Woodruff School of Mechanical Engineering with a joint appointment in the Wallace H. Coulter Department of Biomedical Engineering, said the “wow” moment came for researchers when they introduced a severe influenza virus to the postage-stamp-sized lung-on-a-chip.

Roy and Singh recalled the lung mounting an immune response that closely mirrored what doctors see in patients. Immune cells rushed to the site of infection, inflammation spread through the tissue, and defenses were activated in response. For years, researchers had ignored or struggled to incorporate immunity into organ-on-a-chip systems because the cells often died quickly or failed to circulate and interact with tissue the way they do in humans.

“That was when we realized this wasn’t just a model,” Singh said. “It was capturing the real biology of disease.”

Roy added that the new model fits perfectly into the FDA’s strategic vision to reduce animal testing and develop an innovative new predictive system. “This device goes further than ever before in modeling human severe influenza and providing unprecedented insights into the complex lung immune response.”

Roy added that the new model fits perfectly into the FDA’s strategic vision to reduce animal testing and develop an innovative new predictive system. “This device goes further than ever before in modeling human severe influenza and providing unprecedented insights into the complex lung immune response.”

The researchers said they believe the system can be expanded to study treatments for asthma, cystic fibrosis, lung cancer, and tuberculosis. Over the longer term, they said, it may be possible to personalize the model using a patient’s own cells to predict optimal therapies.

This research was supported by Wellcome Leap, with additional funding from the National Institutes of Health, Carl Ring Family Endowment, and the Marcus Foundation.