In his four years at Vanderbilt, Bill Adcock (then Billy Joe) accumulated several “firsts” as a Commodore athlete.

Not only was Adcock Vanderbilt’s first basketball scholarship recipient, he also became Vanderbilt’s all-time leading scorer and first member of the 1000-point club with 1,190 points (1946-1950). Adcock currently is ranked 30th in all-time scoring in Vanderbilt’s basketball record book.

Adcock was Vanderbilt’s first All-American in 1950. He was named All-SEC for three seasons: First Team in 1948 and 1950; Second Team in 1949.

Adcock (BE’50), recently inducted into Vanderbilt Athletics Hall of Fame with six other honorees, told the audience at the gala it had been his dream to attend Vanderbilt.

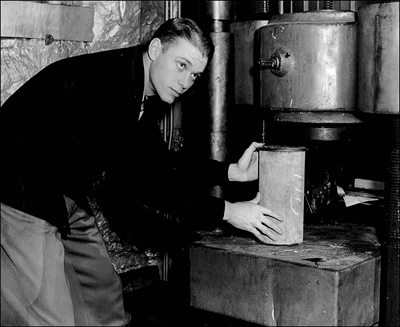

“I grew up on Blair Boulevard, a short distance from the university, but my parents were not able to afford to send me to Vanderbilt. That scholarship helped me fulfill two of my most important goals in life: first, to play basketball at Vanderbilt, and secondly, to study engineering,” said Adcock, whose first job after receiving a degree in civil engineering was with the Monsanto Chemical Company, America’s giant agriculture chemical company. He retired from Monsanto in 1986 after 36 years with the company.

Adcock, who also had taken advantage of mechanical and electrical engineering classes offered during summers, started work in Columbia, Tenn., at a ‘big’ Monsanto plant with about 600 workers. The plant processed elemental phosphorus for use in foods, detergents and fertilizers. “They had six mammoth electrical furnaces to process the phosphate rock,” said Adcock, who was a member of an operations team. “It was the world’s largest elemental phosphorous plant.”

After a three-year stint in Columbia, the company sent him to Anniston, Ala., to run a manufacturing operation on a temporary basis.

Adcock, who had started in manufacturing operations, would move and rise through the Monsanto organization in operations, and sales and marketing positions to eventually become director of corporate sales, and to reside in St. Louis, the company’s global headquarters, where he and his wife, Carol, still live.

“Knowing the machinery proved very productive for me,” said Adcock. “In my plant experience, I met a lot of sales and marketing people. For me it was a natural transition to sales and marketing because I could talk to clients from an engineer’s perspective. I knew how the machines worked.”

For the love of basketball

“I was about 12 years old when I learned to love the game of basketball,” Adcock said. “I was influenced by several high school and college players when I used to slip on the court up at Peabody. I played with a lot of basketball players in the summertime, but my role was solely to fill in when a tenth player was needed.

“In clear terms I was told never to shoot but only to receive the ball and pass it off to someone else,” he recalled. “The neighborhood where I lived had outdoor basketball courts, but my father put in a court with lights in our backyard. Though I liked baseball and football, I played basketball all the time.”

Adcock went on to become a standout basketball star at West End High School. While at West, the school made it to the state championships three years in a row, and in Adcock’s senior year, West’s basketball team was state champion.

Tennessee, Alabama and Kentucky began recruiting Adcock. Kentucky’s Adolph Rupp wanted Adcock for his championship caliber teams. A Nashville basketball official had played basketball for Rupp and tried to influence Adcock to play in Lexington. Though Kentucky was a basketball powerhouse, Adcock wanted to be part of building a program.

Vanderbilt’s pull was strong. “Nashville was my home. I’d followed Vanderbilt sports practically all my life, and I always wanted to go to Vanderbilt and take engineering. I had developed an interest in engineering,” he said.

The Vanderbilt years

“Vanderbilt basketball was not that serious a sport to the university or fans then. The team’s coach was a part-time basketball coach and a full-time football coach. Vanderbilt didn’t have a full-time basketball coach until my sophomore season,” Adcock said.

Also, Vanderbilt didn’t have basketball scholarships in those days. If you received an athletic scholarship at Vanderbilt you were expected to play football, said Adcock. “The scholarship I was offered was really a football scholarship.”

“I received an offer to go to Vanderbilt through the efforts of Willie Geny, a former Vanderbilt athlete who was very active with the local Vanderbilt alumni. When I went over to meet Coach Red Sanders [head football coach and athletic director] to sign up, he told me it was not a basketball scholarship.”

“Coach Sanders said they didn’t have basketball scholarships, and I had to play football as well as basketball. I said, ‘Coach, I really want to concentrate on basketball because that is my best sport, and I want to concentrate on my studies in engineering.’ Sanders said, ‘I’m sorry son, we just don’t give basketball scholarships.’

“That was the end of the conversation and I called Mr. Geny to tell him it looked like I was going to contact Kentucky. He told me not to make any decisions for about an hour and he’d get back to me,” Adcock said.

“I got a telephone call within an hour from Mr. Geny. He told me that Coach Sanders wanted to see me again. I again met with Coach Sanders, and he said, ‘Son, we are going to give you the first basketball scholarship Vanderbilt has ever given.”

Building a basketball team

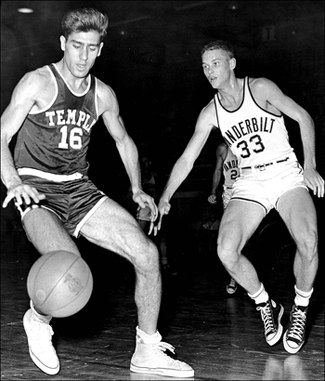

As a freshman in 1946, Adcock would be eligible for varsity play since there was a shortage of players with World War II’s recent ending. With no on-campus gym, home games during Adcock’s tenure were played in gymnasiums at the Navy Classification Center on Thompson Lane, Father Ryan High School, East High School and David Lipscomb’s McQuiddy Gym. Memorial Gym would not open until 1952.

And, as a freshman Adcock played in the game that was considered a “wakeup” call for Vanderbilt basketball. In the 1947 SEC Tournament, the Commodores were humiliated by Kentucky, 98-29. Adcock scored a team-high seven points in that infamous game.

“Rupp made an example of us. He did that on purpose. He was telling Vanderbilt either put up or shut up. Have more respect for basketball or we are going to continue to run you down. We froze the ball the last minute and a half to keep them from scoring 100 points. We got booed off the floor. I thought that the Kentucky fans were going to tar and feather us”.

Adcock said Vanderbilt got serious about basketball, and hired Bob Polk, a Georgia Tech assistant. Polk (1948-58, 1960-61) is Vanderbilt’s third winningest coach (197-106) behind Roy Skinner and Kevin Stallings.

“As far as I am concerned, two significant happenings occurred in 1947 that turned Vanderbilt basketball around. First, Vanderbilt hired their first full-time basketball coach – Coach Bob Polk. Polk started getting recruits from Indiana, Ohio and other places. He was a great recruiter, a good disciplinarian, and he always challenged you as a player. Secondly, Vanderbilt committed to construct a new on-campus basketball gymnasium – today’s Memorial Gymnasium”.

Adcock’s sophomore year was his best. “I made All-SEC that year along with four Kentucky players. It was [Wallace] Jones, [Alex] Groza, [Ralph] Beard and [Dale] Barnstable with me on the first five.”

During Adcock’s junior season, the Commodores were a much-improved 14-8, (9-5 SEC). Polk expanded the schedule and the distances the team would travel for quality games that placed Vanderbilt basketball in the national sporting news.

There were a couple of memorable games for Adcock and his teammates during that junior season. One was an upset in Nashville against No. 6 nationally ranked Tulane and a scoring-record game for Adcock.

“We played Tulane right to the wire,” Adcock said. “They had a lot of gunners and all of them were from Indiana. Their coach was from Indiana. We won in the last minute 56-54 in Nashville. A few games earlier I set the SEC single-game scoring record with 36 points against Mississippi State and that was done at East High.”

The confident Commodores were 17-8 (11-3 SEC) in 1949-50, good enough for second place in the conference. This was Adcock’s final season as a Vanderbilt basketball player.

“In my senior year at Vanderbilt, we came very close to beating Kentucky in Nashville, losing in the last seconds” said Adcock. “After that game, Coach Rupp came over to introduce himself to my father and said, ‘Mr. Adcock, I’d swap my whole team for your son.’ That humbled my father.”

“I always wanted to beat Kentucky, but never did,” Adcock said. “UK was the biggest game and the one we wanted to win the most. I always wanted to beat Adolph Rupp.”

Vanderbilt’s second gift

In the summer after graduation, Adcock played in a college East-West All-Star game in Madison Square Garden. He was one of 10 players on the East squad with future NBA Hall of Famer Bob Cousy as a teammate. Adcock also had a chance to play in the NBA for the Minneapolis Lakers (now the Los Angeles Lakers).

“I never seriously considered playing professional basketball,” said Adcock. “They told me if I made the [Lakers] squad I was going to make $7,500 a year. Minneapolis had five great players and they won the NBA title that year with George Mikan and others. I probably would not have made the first five and possibly not even the second five. I just don’t know.”

“Regardless, I wanted to utilize my engineering background, so I chose to go to work for a growing U.S. company, Monsanto”

Other recognitions Adcock has achieved are memberships in the Tennessee Sports Hall of Fame and the Tennessee High School Sports Hall of Fame, and he is the second Vanderbilt basketball player named as their “Legend of the SEC.”

“Vanderbilt’s outstanding academic credentials opened doors for me that may have never been possible,” Adcock said. “As a result, I began a long and fulfilling business career at the Monsanto Company. The Vanderbilt education and diploma meant the world to me.”

Adcock’s induction into the Vanderbilt Athletics Hall of Fame was a second gift from the university to its first basketball scholarship recipient.

Commodore athletics information was compiled with permission from Nashville sports historian Bill Traughber.