Anti-poaching authorities will soon have a powerful new weapon in their arsenal – high-tech ballistic shockwave sensors under development at Vanderbilt School of Engineering.

The new system, to be integrated with existing commercial tracking collars, would be the first use of shockwave detection technology in the intensified push to thwart illegal trafficking and save endangered African elephants.

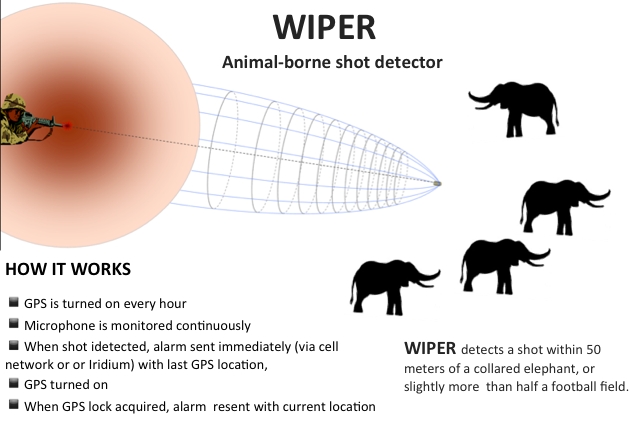

Dubbed WIPER, the project is a joint effort between Vanderbilt computer engineering faculty and Colorado State University (CSU), which has used GPS in tracking collars for years to study and protect elephants slaughtered by the thousands for their ivory tusks. The wireless anti-poaching collars will automatically send coordinates to authorities when a gunshot is detected.

The project got a significant boost Wednesday with announcement of a $200,000 grant from the Vodafone Americas Foundation. WIPER – Wireless anti-Poaching Technology for Elephants and Rhinos – placed second out of eight finalists in Vodafone’s annual Wireless Innovation Project. The awards were announced as part of the 2017 Social Innovation Summit in Chicago.

Project includes Vanderbilt Engineering, CSU, Save the Elephants

For WIPER, Vanderbilt University Professor of Computer Engineering Akos Ledeczi teamed up with longtime elephant scientist George Wittemyer of CSU, who is also Chairman of the Scientific Board of Save the Elephants. The Kenya-based organization is monitoring more than 150 elephants among 1,000 or more it has collared.

Ledeczi’s expertise is in acoustic shooter detection, localization and classification. He and his team have received major grants from DARPA and built multiple wireless sensor nodes to detect and locate the source of gunfire.

“Our aim is to create a open source technology freely available to all collar manufacturers so that it can become a common features in all wildlife tracking devices,” said Ledeczi, who also has received a Vanderbilt Discovery Grant to support the project.

Elephant poachers routinely use devices to muzzle the blast from their high-powered weapons but the blast also produces an acoustic shockwave, which cannot be suppressed. WIPER will detect that a bullet flew by a protected animal and send an alarm with the elephant’s location.

Authorities and wildlife protection groups already use a range of methods to interrupt the ivory trade, including planes and drones that identify poacher blinds, herd hotspots, and animal carcasses. But such systems have limitations. Lower-cost quad-rotor UAVs (drones) can stay up for only 30 minutes so they cannot cover large areas. Fixed-wing UAVs with sophisticated cameras can remain airborne longer but are expensive to buy and operate.

WIPER has significant advantages over existing technology

Animal-borne sensors that track movement speed, or accelerometry, are prone to false positive alerts. Those that send alerts and coordinates when an elephant is immobile are prone to delayed response times – elephants in the wild do sleep, sometimes standing up, for two to four hours most days.

WIPER technology, on the other hand, offers several advantages, especially when used with elephants and other species that range over large areas, Ledeczi said.

WIPER needs only a few sensor collars per herd because each one can cover all wildlife within a 50-meter radius – every sensor adds redundancy and expands the area monitored to include more non-collared elephants that are away from the herd.

“The system does not need to scale with the area but with the number of animals,” Ledeczi said.

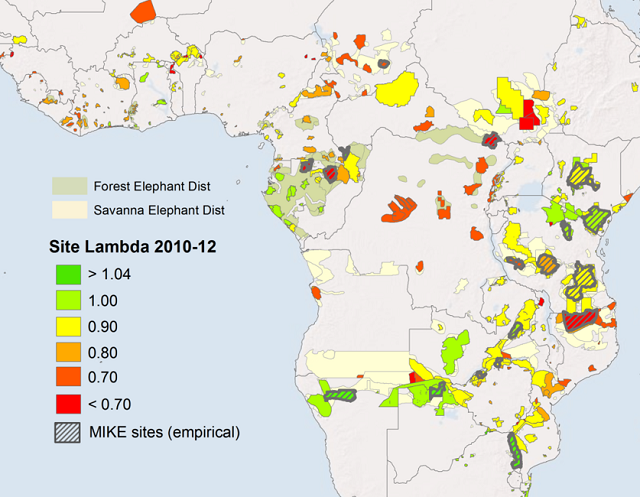

CSU’s Wittenmyer documented the toll poaching has taken on African elements in a major 2014 study. Figures represent estimated rate of decline between 2010-12.

Source: Wittemyer et al. 2014 Proceedings National Academy of Sciences[/caption]

The Vodafone grant will support prototype development and field-testing for shot detection accuracy and power requirements. Next will be integrating the sensor with an existing commercial GPS collar, manufactured by partner Savannah Tracking of Kenya.

Field studies with collared elephants in Northern Kenya follow. The goal is battery power that lasts 12 months. At that point, the team envisions sensor-enabled collars on 100 elephants each year.

The slaughter of elephants and other iconic African animals is fueled by rising demand for ivory in parts of the Far East. As demand increases, prices skyrocket and make illegal trafficking a lucrative, if risky, option. Save the Elephants estimates that 100,000 elephants were killed for their tusks between 2010 and 2012 alone as poaching efforts migrated from the Central African forests to East Africa.

WIPER was one of three projects awarded funding by the Vodafone Americas Foundation this year. Since its start in 2009, the foundation’s Wireless Innovation Project has awarded $5.5 million to researchers whose work uses mobile technology to tackle critical global issues. Vodafone is one of the world’s largest telecommunications providers.

Source: Wittemyer et al. 2014 Proceedings National Academy of Sciences

Media Inquiries:

Heidi Hall (615) 322-NEWS

heidi.hall@vanderbilt.edu