You are walking down the street with a friend. A shot is fired. The two of you duck behind the nearest cover and you pull out your smartphone. A map of the neighborhood pops up on its screen with a large red arrow pointing in the direction the shot came from.

A team of computer engineers from Vanderbilt University’s Institute of Software Integrated Systems has made such a scenario possible by developing an inexpensive hardware module and related software that can transform an Android smartphone into a simple shooter location system. They described the new system’s capabilities this month at the 12th Association for Computing Machinery/Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Conference on Information Processing in Sensor Networks in Philadelphia.

For the last decade, the Department of Defense has spent millions of dollars to develop sophisticated sniper location systems that are installed in military vehicles and require dedicated sensor arrays.

Most of these take advantage of the fact that all but the lowest powered firearms produce unique sonic signatures when they are fired. First, there is the muzzle blast – an expanding balloon of sound that spreads out from the muzzle each time the rifle is fired. Second, bullets travel at supersonic velocities so they produce distinctive shockwaves as they travel. As a result, a system that combines an array of sensitive microphones, a precise clock and an off-the-shelf microprocessor can detect these signatures and use them to pinpoint the location from which a shot is fired with remarkable accuracy.

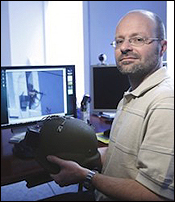

Six years ago, the Vanderbilt researchers, headed by Associate Professor of Electrical and Computer Science Akos Ledeczi developed a system that turns the soldiers’ combat helmets into mobile “smart nodes” in a wireless network that can rapidly identify the location of enemy snipers with a surprising degree of accuracy.

In the past few years, the ISIS team has adapted their system so it will work with the increasingly popular smartphone.

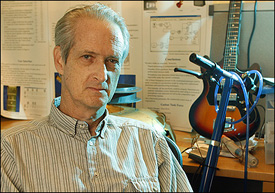

Like the military version, the smartphone system needs several nodes in order to pinpoint a shooter’s location. As a result, it is best suited for security teams or similar groups. “It would be very valuable for dignitary protection,” said Kenneth Pence, a retired SWAT officer and associate professor of the practice of engineering management who participated in the project. “I’d also love to see a version developed for police squad cars.”

In addition to the smartphone, the system consists of an external sensor module about the size of a deck of cards that contains the microphones and the processing capability required to detect the acoustic signature of gunshots, log their time and send that information to the smartphone by a Bluetooth connection. The smartphones then transmit that information to the other modules, allowing them to obtain the origin of the gunshot by triangulation.

The researchers have developed two versions. One uses a single microphone per module. It uses both the muzzle blast and shockwave to determine the shooter location. It requires six modules to obtain accurate locations. The second version uses a slightly larger module with four microphones and relies solely on the shockwave. It requires only two modules to accurately detect the direction a shot comes from, however, it only provides a rough estimate of the range.

The research was supported by Defense Advance Research Project Agency grant D11PC20026.

Contact:

David Salisbury, (615) 322-NEWS

david.salisbury@vanderbilt.edu