In July, Alex Walsh will step up to a podium in Saarbrucken, Germany and deliver a talk on optical metabolic imaging at an international workshop on Advanced Multiphoton and Fluorescence Lifetime Techniques.

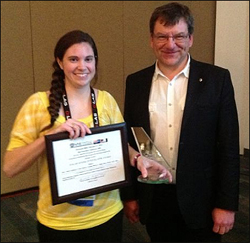

It’s her prize for winning this year’s JenLab Young Investigator Award – one of several awards recently bestowed on the Vanderbilt Ph.D. student.

The same month, Walsh, a 2010 biomedical engineering graduate, will begin work here on a one-year study testing frozen tissue extracted from cancer patients in connection with a student research grant awarded her by the American Society for Laser Medicine and Surgery. She’ll be expected to submit a report on her research and findings to ASLMS’ journal, Lasers and Surgery and Medicine (LSM). Walsh will receive $5,000 in funding for her project, “Optical Metabolic Imaging of Organoid Cultures Derived from Frozen Tissues to Predict Drug Response.”

In a triple play of distinctions, Walsh, 24, also was honored this spring with a Graduate Research Fellowship from the National Science Foundation. With it, her Vanderbilt research team will continue its work “trying to develop a screening technique for cancer drugs and their effects on patients, to see what drug they are responding to.”

“You expect every patient to react differently to drugs. The goal is to target a drug or combination of drugs to a specific cancer cell,” said Walsh. “We are developing a way to take a piece of tumor and grow it in cultures, then treat it with a whole bunch of drugs to see what drugs the patient is responding to.”

Walsh came to Vanderbilt in 2007. At that point all she was certain of was the fact that she didn’t want to go to the University of Texas in Austin. She grew up in Austin where both parents are engineers and where her grandfather, Ashley “A.J.” Welch, was a professor of electrical engineering – best known for his early work on laser safety and who helped lay the groundwork for laser and tissue interaction.

Now as professor emeritus, A.J. Welch is involved in the field of medical optics, his specialty being the optical thermal response of tissue to laser radiation.

Alex thinks it’s serendipitous that in some ways her research mirrors that of her granddad.

“When I was growing up I never realized he was a big deal. He’s very humble; never talks about his accomplishments,” she said. “I will say I was afraid of being pressured into going to Texas. So I didn’t even apply. I knew I would get in, and there would be a lot of pressure to go and follow granddad.”

Her grandfather recognized that when Alex was in high school she showed a keen interest in math and science, and while she notes that pretty much every kid who does well in math and science wants to be a doctor, everybody in her family was an engineer. “So, everybody said, ‘Go be an engineer’,” she recalled.

It was then the journey to Vanderbilt began in earnest. Walsh remembers that her grandfather used to host international students for dinners at his house and she attended some of them. She remembers one dinner with a pair of biomedical engineering graduate students who had met on campus in Austin and soon were married. Later when Walsh asked about Vanderbilt as a school choice, her grandfather put her in touch with some former students there. It turned out to be the dinner guests in Austin, Anita Mahadevan-Jansen and E. Duco Jansen, both professors of biomedical engineering.

“I had always remembered them. They had so much good to say about Vanderbilt,” she said.

Walsh became entrenched in the School of Engineering, with one undergraduate diversion to university athletics when she swam competitively on the Commodores swim team from 2007-2009. She has been the recipient of numerous honors, including the Provost Graduate Fellowship Award, Vanderbilt University [2010-15], the Air Force Office of Scientific Research Grant [2013], Young Investigator Award, Frontiers of Biomedical Imaging Science III, [2011], award for Top Peer-Reviewed High-Scoring Abstract, Host-Tumor Interactions Program & Department of Cancer Biology Retreat, Vanderbilt University [2011], U.S. Air Force Travel Grant Recipient for presentation of work at ASLMS [2010], and the aforementioned grants.

The ASLMS grant is where her focus is currently – doing testing on frozen tissue, basically trying to answer the question: ‘Can you freeze, thaw and test tissue?”

“We want to revive frozen tissue to get meaningful results and then determine what is the best way to freeze the tissue – that’s what the grant is about,” Walsh said.

Tissue size determines how many drugs you can test and how many cultures you can grow, she explained. From a small piece (couple millimeters) of tissue you can grow hundreds of cultures, then you can test a whole bunch of different drugs. It is a non-invasive procedure, and the tissue is not harmed. However, the key difference with this method over current practices, according to Walsh, is that researchers now use genetic screens, where they extract DNA from a group of cells and look for genes that have been mutated. From there they infer what drugs may be working based on percentages and probability. “Since we are doing imaging, we can view individual cells.”

“The unique thing about ours is combining the growing of cultures with the optics. It gives a faster readout and hopefully more specifics,” she said. “For breast cancer, there are 50 or more FDA-approved drugs, but we may be able to say some don’t work that well. And more importantly, we can better identify which one does works better for a specific individual.”

While Walsh can be very specific in detailing her current endeavors, at times even using paper and pencil to draw illustrations to enlighten the curious, her future plans are uncertain.

“I still don’t know what I’m going to do, but I like that I have lots of options,” she said. “I think about going into practical medicine, and I thought a lot about being a doctor while I was in high school.”

Walsh smiled as she mentioned that in research you just make more questions as you answer the ones you originally set out to answer. Then she said, “You know as recently as last week I was thinking about being a radiologist.”