By Vincent Troia

For a brief moment half a century ago, four Vanderbilt University engineering students were band mates in ‘Nashville’s Most Popular Combo.’ How they managed to attain that title is a longer story – one that was recently recounted as if it happened yesterday.

As the Lancers, Logan Hickerson (saxophone), Gene Kirby (drums), Harry Moore (lead guitar), and Phil Hendrickson (bass, keyboards, rhythm guitar, vocals) were doing well for themselves – earning spending money, playing frequent gigs, winning competitions. And they all did it while earning degrees (BE’65) in civil engineering.

Playing in the pre-Beatles rock/rhythm & blues era, the Lancers borrowed largely from the black artists of the day – Muddy Waters, Ray Charles, Jimmy Reed, Bo Diddley – music they heard on disc jockey Hugh Cherry’s radio show on Nashville’s WMAK.

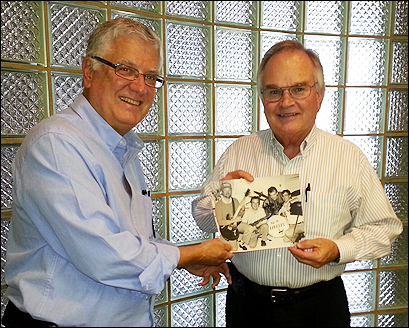

- Gene Kirby (left) and Logan Hickerson reminisce about The Lancers and their days in the engineering school.

“The station played what the kids liked to dance to,” remembered Hickerson. “So we were riding along with that. When we started it was rhythm and blues; when we finished it was rock ‘n’ roll.”

WMAK was one of Nashville’s two most popular radio stations (WKDA the other) among listeners aged 18-49 during the late 1950s and through the ‘60s. During this period, the two battled for supremacy of the airways by trying to outdo each other in contests, or with the most music, or with the coolest DJs. Cherry was one of those.

Kirby recalls going out to buy the 45-rpm records played on the radio, having the band gather around a record player, listen and try to figure out how to play it. Ultimately, it was Hendrickson who could put it together for them.

“The guiding influence for our song selection was Phil’s obsession with listening to WMAK,” said Hickerson. “We didn’t write our own music or anything like that – it was copycat stuff, but we definitely had our own style.”

He thinks the band members borrowed a bit from jazz, since they we were able to improvise so well. “It is hard to describe how that can work so seamlessly but it did. Call it chemistry, or synergy, or whatever it is, we had that,” he added. “As engineers, we experimented I guess, but we still can’t figure out how we did it.”

He thinks the band members borrowed a bit from jazz, since they we were able to improvise so well. “It is hard to describe how that can work so seamlessly but it did. Call it chemistry, or synergy, or whatever it is, we had that,” he added. “As engineers, we experimented I guess, but we still can’t figure out how we did it.”

The band came together by accident when all four boys were in the same high school fraternity in 1958. Kirby became close friends with Harry Moore who just happened to own a guitar – and also spent a lot of time with his ear glued to Nashville radio.

“While our classmates were happily listening to Elvis (Presley), we were listening to Mississippi Delta and Chicago blues of the day,” Moore said. “I think we were smitten with that sound and emotion, and later, as the Lancers, blues music was our passion.”

Listening to Moore play prompted Kirby to “learn to play something,” so he went to a pawnshop and found a set of drums.

Since two-piece bands would not be popular until the White Stripes or Black Keys made them so decades later, Hendrickson was asked if he wanted to play with the other two. Things started to gel, but something was missing.

Kirby, by default the group’s leader/promoter/manager, spotted Hickerson in the audience at a Belle Meade gig where the then-trio – initially called BH and the Betas – was playing. Before the fraternity, the two had met years earlier at a Lipscomb University day camp.

“I knew he played saxophone, so at the Belle Meade party, I saw him in the crowd and recruited him,” Kirby said. That core group has endured for 50 years.

Nashville’s Most Popular Combo

At the top of their game, the Lancers had a 90-song playlist and could perform 31/2 or 4-hour sets. The band played mostly weekends, from National Guard armory shows and Hugh-Baby Hops to school dances or fraternity and sorority parties. But it was at one of Father Ryan High School’s benefit ‘battle of the bands’ competitions that the band earned its proudest moment.

“The talent shows were a big deal and we had lots of competition,” Hickerson recalled. There were celebrity judges, television cameras, the press, and some very good local bands.

There were the Sliders, who had won in previous years, the Gators, and ‘car-tagged’ groups the Fairlanes, the Impalas and the Monarchs. In fact, Hickerson remembers that with so many groups using car model names, the band followed suit, choosing a new model Dodge – the Lancer – which members thought looked pretty sharp, as its moniker.

Speaking of “sharp,” the competition for gigs and contests require band members to look that way too.

“We knew we needed to clean up our image, so we went down to this little shop in The Arcade downtown where the owner told us ‘I’ll take care of you guys. I dress all the bands. I’m going to make you look sharp.’ And he did,” Hickerson said.

Kirby found one of the thin little ties (‘Like the Beatles wore’) in his dresser not long ago.

“We looked like the Four Tops; had gray blazers; had black jackets with silver threads all through it,” he said. “If you watched “American Bandstand” around that time, we all looked like that.”

- Although now scattered from Franklin, Tenn. to Switzerland, the Lancers would still get together from time to time to practice, as they did in this 1980s photo. L-R, Harry Moore, Logan Hickerson, Phillip Hendrickson and Gene Kirby.

The Lancers claim to have dazzled the judges in 1962 at War Memorial Auditorium, taking home ‘Nashville’s Most Popular Combo’ honors, a title that thereafter adorned the band’s business cards. However, Moore believes the win “was only due to our (then) girlfriends stuffing the ballot box at the contest.”

Even though band members went to four different high schools and kept the band together, when they attended Vanderbilt at the same time, it was harder to find practice time or play gigs. While they held together for awhile, school eventually won out.

“It was just a stroke of luck that we all ended up at Vanderbilt,” said Kirby, who had applied to University of Tennessee as well. Other mates hoped to go out of state.

Moore applied to Dartmouth, though it was no surprise he wound up at Vanderbilt.

“I have a strong Vanderbilt heritage. My mother, brother, aunt, cousin, and niece all went there,” Moore said. “I was introduced to all things Vandy, starting with football game attendance with my parents at about eight years old. After high school, engineering school just felt like the correct career path.”

The band mates played together from 1958 when they were high school sophomores until they each received bachelor of engineering degrees in 1965. (Moore thinks it’s cool that his degree and his Fender Stratocaster both carry a ’65 date.) From there they pursued jobs, master and doctorate degrees, plus marriage and family. Hendrickson earned a Ph.D. in optical physics; Moore a Ph.D. in environmental engineering from Vanderbilt. All of them went on to enjoy successful careers and the infrequent reunions.

Vanderbilt may have proved the endpoint to the Lancers musical path, but Hickerson says the university experience paved the way for his future in ways the band never could.

“My first two years (at Vanderbilt), my record was atrocious. The band was able to help me – it absolutely helped me,” he said. “I initially gave up the band because I thought I needed to focus more on improving as a student. But I realized I had given up something that was a lot more important to me than I thought, so I found a way to make it work.”

“My first two years (at Vanderbilt), my record was atrocious. The band was able to help me – it absolutely helped me,” he said. “I initially gave up the band because I thought I needed to focus more on improving as a student. But I realized I had given up something that was a lot more important to me than I thought, so I found a way to make it work.”

Moore remembers that as tight as the band was during gigs on the weekend, the four of them were just as tight during the week working together in their own study group, tackling structures, thermodynamics, differential equations… or prepping for an upcoming exam.

“I will never forget when the four of us were studying for a test in an engineering classroom the day President Kennedy was assassinated,” Moore said. “We were serious engineering students and considered ourselves very fortunate to be learning from faculty members Bill Rowan, Peter Krenkel and Walter Graham, among other fine teachers.”

Moore says it is no secret that the band members carved out successful careers bolstered by all that they learned at Vanderbilt.

“Looking back, I think I learned how to compromise and work closely with business teams by being in the band,” Hickerson said. “It was work, but it didn’t feel like it. It was fun. So I learned to make sure work had some element of fun.”

‘Fun’ was the component that solidified the combo from the beginning. Hickerson says academics always were the priority; the band was a way to have some fun and earn some spending money.

According to Kirby, the band was earning $100 a show when they started out, but sometimes The Lancers would just play and not worry about the money.

“We played a hop in Gallatin and got paid $30 after driving all the way up there,” Kirby said. “Most of that went for gas. But we had a lot of fun; there were a lot of girls up there.”

Kiss your allowance goodbye

The Lancers got paid twice as much to play up in Sewanee once or twice a year. Kirby remembers great shows there, with lots of kids dancing to early rock ‘n’ roll that was fairly new to them.

“We did OK getting paid,” said Hickerson, recounting a favorite dinner-table story. “One time at dinner, my brother and father and I were sitting around, with my dad behind a newspaper, and I asked a question about if I needed to be doing something about income taxes. My father looked up from the paper, said ‘I don’t think so,’ but then asked how much I made.

“Now I don’t remember what the figure was, but when I told him, he sat there for awhile and said, ‘You made how much?’ My brother was listening intently. The amount was more than he made in a week at his job. My dad said, ‘I pay you a $1 a week for allowance, don’t I?’ When I nodded, he said, ‘Well, you can kiss that goodbye’.”

Hickerson may have lost the allowance but The Lancers had earned local recognition and lifelong friendships that continue to this day. The band played a few reunion gigs over the years – the most notable one at a 1993 outdoor music festival in Switzerland, where Hendrickson has lived for years. They played outside at an old mill near the Rhine, where trailer stages containing the loudest sound system the band ever played with were trucked in.

Hickerson may have lost the allowance but The Lancers had earned local recognition and lifelong friendships that continue to this day. The band played a few reunion gigs over the years – the most notable one at a 1993 outdoor music festival in Switzerland, where Hendrickson has lived for years. They played outside at an old mill near the Rhine, where trailer stages containing the loudest sound system the band ever played with were trucked in.

And their legacy lives on in strange ways, according to Hickerson.

“Sometimes in a band, you have your circle of friends. But when you play to a large group, you have people you never set eyes on, but they’ve been watching you,” he said. “It’s funny because, even 20 years after we played around here, I might get on an elevator somewhere and some guy might ask ‘You still playing saxophone?’ It’s the darndest thing.”

It also can lead to business opportunity, such as the time Hickerson was able to get the late Nashville doctor and businessman Thomas Frist, Sr. to invest in a residential development his company was building in Rutherford County.

“Around 1982, I was in an appraiser’s office, and a guy there remembered me from the Lancers,” he said. They struck up a conversation that led to Dr. Frist’s involved.

“That was a lick we would not have had if not for the band,” Hickerson said.

With the band members turning 70 (Kirby is holding on to 69 for a few more months), all the stories of the Lancers are recounted in conversation. In the new internet millennium of YouTube and Instagram, Facebook and digital music archiving, do they regret not having any of their songs or set lists or concert photos saved for posterity?

“Not really,” said Hickerson with a slight snicker. “The way you remember it, and the way it was can be two different things.”

He was quick to point out that the Lancers did a lot of improvising in their shows. There was a synergism that tied them together, with each musician unconsciously knowing where the others were going, so Hickerson thinks even a recording or two wouldn’t give an accurate measure of the band. And he remembers why.

“Harry once said that we had one true distinction in that we never played the same song the same way twice.”