What does a young boy do when he wants to play sports but the helmet interferes with his cochlear implants? What about a Vanderbilt student who can’t carry her own meals because she needs both hands for a walker? Or another student who uses a wheelchair wants to hold a door open for a friend but cannot because it closes quickly behind her?

In each case, students in a new DIVE course got to work solving the problem. Teams of sophomores and juniors took on “clients,” which included the young sports fan, two Vanderbilt students, and Thistle Farms, a Nashville nonprofit organization.

“How to Make (Almost) Anything,” modeled after a popular class at MIT, was offered in fall 2017 for the first time. Kevin Galloway, Design as an Immersive Vanderbilt Experience (DIVE) director, will teach the class again in the spring.

Students assess needs, come up with three potential solutions, evaluate the options, then design, prototype, and test the top contender.

The class is open to sophomores and juniors of any discipline and builds rapid prototyping skills students can apply to future classes and personal projects, said Galloway, who is also a research assistant professor of mechanical engineering and Vanderbilt’s director of making.

In this first class, more than 50 percent of the students were computer science majors. And female students outnumbered their male counterparts.

Giving form to an abstract idea provided lessons both expected and unexpected.

“The first idea rarely works,” Galloway said. “Part of it is learning to get over that quickly.”

Two of the projects were done in partnership with the Next Steps program at Peabody School of Education. For one, a team of computer science majors designed a walker extension to hold a dining hall tray. It needed to be strong, easy to use, lightweight and aesthetically pleasing.

Because the walker is wider than the tray, the team had to make several adjustments. But the goal was met – increased independence for the client, who wanted to get from the dining hall lines to a table without asking someone to carry her tray. (See recent News Channel 5 coverage on this project).

Another client, who uses a wheelchair, told her engineering team she wanted to be able to open push bar-type doors on campus. During the discovery phase, the team encountered multiple complications but also gained an important insight.

Student engineers had hoped to find fairly standard door components across the campus. They did not. The width of doors varied. The size of push bars varied, too, as did their height on doors.

But the big pivot came when the client realized she could push doors open herself.

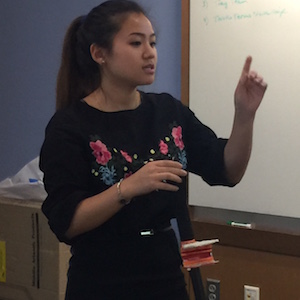

“What she wanted was a device that can help her friend who uses a walker get through door behind her,” said Robbie Crawford. “She wants to be someone who can help others, too, but the door closes on her really quickly.”

In the end, the team fashioned a stick-like device with a clip that fits on the push bar and a door stop at one end. “She’s excited about how this can be part of her life,” said Margaret Oh.

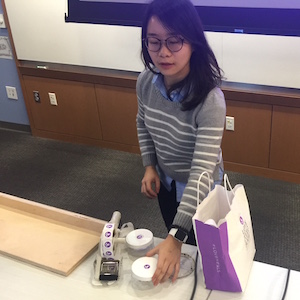

The Thistle Farms project involved creating a device that made manually placing stickers on the centers of jars more efficient – without automating the process so much that it eliminated a job. The non-profit provides safe housing and job engagement for survivors of trafficking, prostitution and addiction. It produces popular lines of aromatherapy home and skin products sold worldwide.

“We looked at existing devices, including a handheld sticker gun made for inventory,” said student Eric Douglas. “It is fast but the stickers aren’t centered. Thistle Farms wants to keep the human element, and wants to keep the women engaged with the production of goods.”

Ease, safety, cost-effectiveness and sustainability underpinned all the projects. The team trying to fashion a sports helmet that works with a cochlear implant faced multiple challenges, including the lack of any similar product already on the market.

The students made prototypes of three ideas – a malleable “sub-helmet,” a helmet with a butterfly flap, and a helmet with a spring hinge that snapped in place. The hinged option seemed the best approach, though the team continued to work on sizing the hinge and making the helmet easier for Logan, the client, to put on.

“We weren’t making it more comfortable but we definitely weren’t making it less comfortable,” said Emily Larson.

The team presentation included a short video clip of Logan putting on the helmet, though he struggled with the clips, and later talking about the process. It wasn’t ready for real use but was nearing the point of some field testing.

“Thank you for making it,” Logan told the team.