Twice in 2019, Nick Adams and his colleagues applied for federal grant money to develop a rapid, precise, in-office test for respiratory infections. This test would skip the time-consuming and expensive steps of purifying the samples for testing or sending them to a lab. Doctors and their patients would not have to wait days, sometimes weeks for results.

Their proposal got high marks for innovation. But the reviewing panel at the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, part of the National Institutes of Health, questioned its significance. Among the comments: Existing tests worked fine for diagnosing seasonal flu and pneumonia. What’s wrong with sending samples to a lab?

What a difference a year makes.

In June 2020 the reviewers were more receptive, and in September the NIAID awarded the team a five-year grant of nearly $4 million to develop a panel of quick tests to diagnose COVID-19 infections, seasonal flu and other respiratory illnesses. Adams, research assistant professor of Biomedical Engineering, had updated the application with information about the COVID-19 pandemic, shortages of testing components and an anticipated surge in demand for more widespread, frequent testing.

“Despite the initial funding rejections, we are fortunate to have continued to work toward developing a better test for respiratory illnesses,” Adams said. “We knew we had a good idea, but I guess we just had to wait for others to recognize it!”

Eliminating bottlenecks

The multi-investigator award acknowledges the interdisciplinary nature of the work, with three researchers sharing equal responsibility and workloads: Professor of Biomedical Engineering Frederick Haselton, an expert in instrumentation and device development; Dr. Jonathan Schmitz, medical director of the Molecular Infectious Diseases Laboratory at Vanderbilt University Medical Center; and Adams, whose specialty is molecular biology and assay development.

The team’s key innovation detects diseases without needing a purified sample of molecular material. The approach replaces extraction and purification, as in done in traditional polymerase chain reaction, or PCR, with a simple heat activation step. It eliminates the need for expensive extraction reagents, which have been a source of COVID-19 testing bottlenecks. And the method, called adaptive PCR, uses the Centers for Disease Control’s recommended primers, or “master mixes,” for SARS‐CoV‐2 testing.

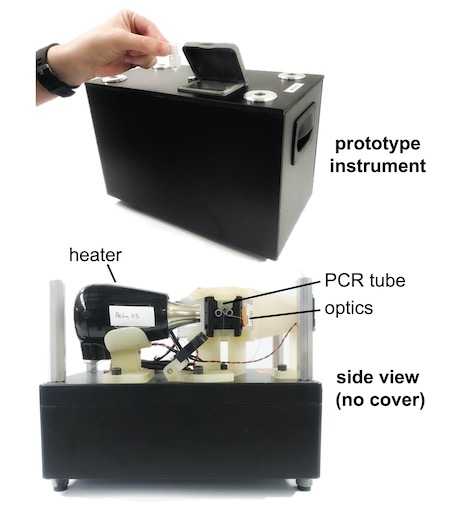

First, the team will evaluate the performance of the approach using traditional equipment and then a prototype they developed of adaptive PCR equipment, which is designed for portability and use in physician offices, acute care clinics and low-resource settings.

Saving time and money

Recent findings from the team’s related pilot study suggest that laboratories now, if faced with reagent shortages, could use unextracted samples for symptomatic COVID-19 testing with minimal diagnostic impact.

“You can save time and money and address pandemic a lot better if you skip the extraction step using the protocol we’ve come up with,” Adams said.

Comparing the use of extracted and unextracted samples found little difference in detection of the virus in samples of symptomatic patients. With virus-negative samples, the adaptive PCR method was just as accurate as traditional PCR.

The study was published July 23, 2020 in the Journal of Medical Virology. It follows the team’s successful similar tests with malaria.

“We have a good idea of how this testing method could help today but haven’t been able to gain traction with people who could implement it,” Adams said. “We’ve shown you can get really good diagnostic results without extraction using our method. It’s not proprietary, and there’s nothing that would prevent someone from being able to use it anywhere.”

Testing anywhere–without a lab

The five-year, $3.9 million project builds on this previous work by expanding testing to the point-of-care, which is enabled by the portable, adaptive PCR instrument. Beyond SARS-CoV-2, the team will develop a respiratory panel that detects four other viruses–influenza A and B, respiratory syncytial virus and rhino virus; two bacteria–Chlamydia pneumoniae and Mycoplasma pneumoniae, which cause similar respiratory symptoms; and one control target. The ultimate goal is a small device that can be used anywhere.

Successful completion will result in “a novel point-of-care tool for both the established and emerging respiratory infections” that threaten public health, facilitating rapid treatment, follow-up, infection prevention and epidemiologic containment.

“We’ve seen reports on shortages in testing and delays in getting results,” Adams said. “They’re going to roll out a vaccine soon, and when they do, they will want to test people to see if it is effective.”

“Testing is going to be used even more in the future. How are we going to keep up with testing then if we can’t keep up now?” Adams said.

Related stories:

DNA duplicator small enough to hold in your hand

BME team develops quick DNA test for malaria drug resistance