By Marissa Shapiro

THE IDEA

The human brain is organized in functional networks—connected brain regions that communicate with each other through dedicated pathways. That is how we perceive our senses, how the body moves, how we are able to remember the past and plan for the future. The “default mode” network is the part of our connected brain that is responsible for abstract and self-directed thought.

When we process external sensory information, the default mode network turns off, and when there is less going on outside our bodies it turns on. Whether the same default mode network is found in mammals similar to humans has not been firmly answered; different studies have yielded different conclusions.

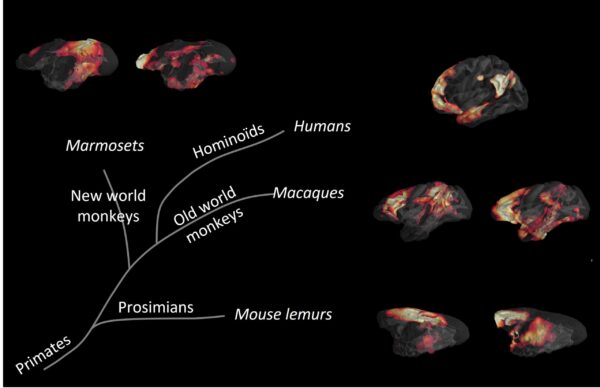

In an international collaboration across seven laboratories, in five institutions, across three countries and led by Christos Constantinidis, professor of biomedical engineering, neuroscience and ophthalmology, and Clément Garin, postdoctoral fellow in the Constantinidis lab, researchers compared data from humans and non-hominoid primates (macaques, marmosets and mouse lemurs) to more definitively answer this question.

“Surprisingly, our results showed that in all species other than humans, the brain areas that comprise the default mode network involve two systems not strongly connected with each other,” Constantinidis said. “These regions, one responsible for suppression of external events and one for more cognitive tasks, appear to be linked only recently in evolution. It is this linkage that may have facilitated the capacity for abstract thought that led to the rapid evolution of human cognitive abilities.”

WHY IT MATTERS

The unexpected finding changes the way we think about brain networks. Atypical patterns of connectivity between brain areas are signatures of neurodevelopmental disorders and mental illnesses. These conditions are a significant health and societal issue that affects individuals’ ability to healthily function in society. Understanding how unusual patterns of brain connectivity emerge could lead to better diagnosis and treatment of these conditions, Garin said.

WHAT’S NEXT

Next steps of this research will focus on how brain networks normally mature in childhood and adolescence and what goes wrong in mental illnesses, many of which emerge in early adulthood, Constantinidis said.

FUNDING

This work was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health grants R01 MH116675 and R01 MH117996.

GO DEEPER

The article, “An evolutionary gap in primate default mode network organization” was published in the journal Cell Reports on April 12.