“This trip made me want to be an engineer.”

Best feedback ever from a youngster on a fieldtrip, according to staff leaders at Vanderbilt Engineering’s Laboratory for Systems Integrity and Reliability.

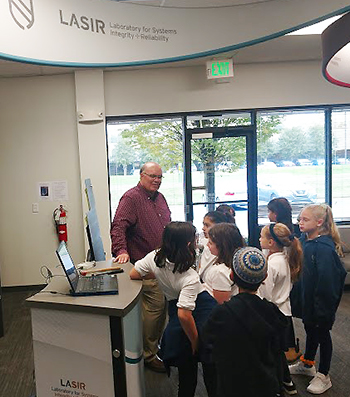

Eight fourth graders from Nashville’s Akiva School recently toured the engineering school’s super-sized, high-bay lab in Metro Center, located along the Cumberland River near downtown.

Beginning in the lobby of LASIR’s 20,000 square-foot facility, the students gathered around the popular ‘touch table’ display and the three kiosks that illustrate the lab’s major research thrusts: security—staying ahead of threats to our infrastructure; energy—meeting the energy demands of a growing population; and manufacturing—optimizing a new generation of products. From there, they entered the lab to see projects on a large scale.

Favorite activities: Hit the helicopter, smack the speed bump, stand near the wind tunnel, and peek through a section of a full-scale wind turbine blade.

Smacking the “smart cleat” proved entertaining. The cleat looks like a portable speed bump but it actually detects vehicle damage.

In the aftermath of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, the Department of Defense shipped large numbers of used military vehicles back to the United State and had the daunting task of determining which vehicles are worth reconditioning and which should be scrapped.

LASIR researchers developed an instrumented steel speed bump that can determine how seriously suspensions and drive trains are damaged by vibrations as vehicles drive over the cleat.

Students took turns hitting the cleat and watched indicators jump on a nearby monitor. “I liked the things that you hit because it’s fun to hit things,” an opinion seemingly held by all the youngsters.

A CH-53A Super Stallion heavy-lift helicopter airframe captured everyone’s attention, not only because of its sheer size but also because the students scrambled in and out of the copter.

“My favorite part of the tour was when we got to go into the helicopter because I got to kind of experience what my dad got to fly,” said one youngster.

Students were encouraged to hit the copter’s outer skin with a small mallet and they learned that unlike metal, composite airframes don’t dent when hit by birds or debris and that damage can’t be determined visually. Composites are stronger and lighter but it is much harder to locate damage.

LASIR researchers have developed inertial sensors that are embedded in sections of the composite skin. The location and strength of the hits are displayed on another nearby computer monitor.

“My favorite part of the tour was the cargo helicopter with sensors to identify damage because it was really cool to see an Army cargo helicopter that had actually been flown.” But, “going inside” the copter was slightly more popular than swinging the mallet.

The energy demo is a project to control the yaw of commercial wind turbines more accurately. Currently, wind farms determine the direction their turbines should point by maximizing the amount of power that they produce. However, if the wind shifts by 5 or 10 degrees, the power output barely budges but the stress in the blades rises dramatically.

The lab’s shed-size wind tunnel where blade research is conducted proved to be a sensation, especially when the turbines fired up. “I liked the wind tunnel [chamber] because it looked so cool and the wind turbines were going super fast,” said one admirer.

The fourth grade students in teachers Annette Calloway’s and Susan Eskew’s class recently read The Boy Who Harnessed The Wind while investigating alternative and renewable energy sources. The students designed, tested and improved solar ovens and one student created a hydroelectric claw to test waterpower.

In May of 2019, Akiva School received its STEM/STEAM certification from AdvancEd, Cognia. They are the first Jewish Day School in the world to receive this certification. Akiva received an in-depth third-party review, detailed analysis and feedback into where their school excels and where to apply resources in continuing their pursuit of excellence.

“Students in K-6 use the Engineering Design Process when faced with a problem or need. They use engineering habits of mind and STEAM mentor texts,” Calloway said. “We wanted to extend their learning by visiting LASIR.”

LASIR staff members agreed they couldn’t have said it better than this young visitor:

“I think it is important to make things safe so you can protect people while accomplishing amazing things.”

Contact: Brenda Ellis, (615) 343-6314

brenda.ellis@vanderbilt.edu