The lab of Ethan Lippmann, assistant professor of chemical and biomolecular engineering and biomedical engineering, seeks to model, understand, and ultimately treat neurodegeneration, focusing primarily on the blood-brain barrier, a border of protective blood vessels found in the brain.

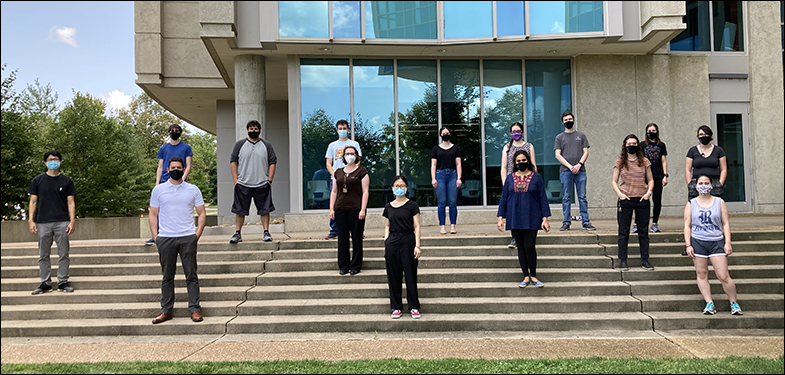

Before the COVID-19 pandemic, Lippmann’s team in the Neurovascular Engineering and Therapeutic Design Laboratory was firing on all cylinders, having just completed onboarding new personnel and doubling in size over one year to include eleven graduate students, two postdocs, and two research staff, all of whom felt the impact of the lab’s sudden closure on both their research and the team’s sense of community.

“They were pretty disheartened when we had to shut down,” said Lippmann. “One of the joys of having a large lab is supporting diverse research, and it was frustrating to see how much this affected the work of students who are just beginning their careers. One of my first graduate students defended her Ph.D. thesis in February and was matriculating into the School of Medicine to pursue an M.D. in the Medical Innovators Development Program. We were finishing up on a couple of papers and collecting capstone data for a couple of grants, and then— shut down. We couldn’t finish some work that was critical to her dissertation.”

When Lippmann’s team had the opportunity to return to the lab in Phase I of Research Ramp-up, he emphasized that no one was under any obligation to do so if they did not feel safe, but everyone was eager to get back to work, committed to fighting central nervous system diseases through innovative research. Phase I capped lab occupancy at 33 percent, so the team returned in shifts to restart cell cultures and analyze samples. “It was a limited amount of work but an anchor in a sea of uncertainty,” said Lippmann. “They could get out of their apartments and homes, come to a place where life felt a little more normal and familiar.”

Now in Phase II+, the team operates at 50 percent capacity, splitting shifts so that they each have a half day in the lab every day. That time is critical to everyone’s research since they are a wet lab and 90 percent of their work can only occur on campus.

Some personnel also use equipment in collaborators’ labs, and to ensure they are following physical distancing protocols, they are creative about how they access them. For instance, graduate student Allison Bosworth takes time on the weekend to use a particular microscope in David Merryman’s lab because the room in which it is located can only fit one person at a time and is in use by Merryman’s team throughout the week. Lippmann’s lab is highly collaborative with others, working together to safeguard spaces so that everyone’s research can advance.

That cooperative spirit is a hallmark of Lippmann’s team. Before the pandemic, it manifested itself in inconspicuous ways. A coffee enthusiast, Lippmann always purchased the beans for the entire lab and even supplied a $1000 espresso maker, but he was mindful of keeping the coffee pot in the students’ office, a gesture symbolic of the lab’s close community and his style as an advisor to prioritize an affable rapport with his advisees. Frequent trips for refills made it easy for Lippmann to learn about the progress of students’ projects by engaging in spontaneous, face-to-face interactions.

Slack and Zoom have replaced those interactions, with students occasionally appearing in the doorway of Lippmann’s office, keeping their distance, wearing masks, never staying longer than needed to discuss their research. Sometimes they will pull up a chair to review data with Lippmann, which he displays on a large TV in his office to maintain proper physical distance, but impromptu discussions have become much less frequent.

Those now occur on Slack, like on their crafting channel where many of the graduate students share pictures of their quarantine hobbies of baking and knitting. Lippmann credits the lab’s graduate students for continuing the amicable office culture in remote spaces, but it began when labs shut down, causing home and work life to intertwine.

To lift the team’s spirits, Lippmann started sharing pictures and videos of his one-year-old daughter on Slack. While these small acts of social engagement may seem trifling to the team’s research aims, they are important for coping through a difficult year and maintaining team continuity.

“We may not be able to interact with each other as we once did but returning to the lab has made us feel like we are working together toward a larger goal,” said Lippmann. “We can read papers all we want in quarantine, but that just makes us want to get back to work and test ideas. I am grateful to my team for strict adherence to safety protocols. It reflects their dedication to ensuring that we can continue to fight neurodegeneration through innovative research.”

By Jenna Somers

This story is part of a series highlighting Vanderbilt University researchers who have returned to in-person research activities on or off campus. More than 3,000 Vanderbilt research personnel, including Ethan Lippmann and his team, have returned to in-person research activities through the Research Ramp-up process spearheaded by the Ad-Hoc Research Ramp-up Working Group and the Office of the Vice Provost for Research.

Contact: Brenda Ellis, 615 343-6314

brenda.ellis@vanderbilt.edu